ROTATOR CUFF DISEASE

WHAT DOES THE ROTATOR CUFF DO?

WHO GETS ROTATOR CUFF TEARS?

HOW DO I CLINICALLY DIAGNOSE A CUFF TEAR?

WHO NEEDS AN MRI?

DOES EVERY CUFF TEAR NEED TO BE FIXED?

WHAT DOES ROTATOR CUFF REPAIR INVOLVE?

ARE THERE ANY OTHER SURGICAL OPTIONS?

WHAT DOES THE ROTATOR CUFF DO?

The rotator cuff is made up of subscapularis (anterior), supraspinatus (superior), infraspinatus (posterosuperior) and teres minor (posterior). The main function of the rotator cuff is actually concavity compression, or keeping the humeral head compressed towards the glenoid during active shoulder motion. A secondary function is contributing to shoulder motion - internal and external rotation, abduction, elevation.

WHO GETS ROTATOR CUFF TEARS?

Rotator cuff tear patients generally fall into two main groups: 1) Degenerative tears

2) Traumatic tears

Degenerative tears tend to occur in patients in their 60s and older (sometimes in their 50s) and are usually the end stage of a chronic process of tendon degeneration, repeated microtrauma to the tendon and small partial tears. Impingement may also contribute to tendon attrition. A degenerative tendon may go on to full-thickness tearing after a fall or other trauma, but the tendon was not normal before the trauma.

Impingement and subacromial bursitis

Degenerative rotator cuff tear

Traumatic tears can occur in any age group, but it is important to consider the younger patient (under 50), who has a distinct traumatic episode and has new shoulder pain or inability to raise the arm after that trauma, as a separate entity to the degenerative cuff tear patient. These patients usually had a normal rotator cuff tendon complex prior to the trauma, and can therefore be expected to have better tendon quality than the degenerative tears, allowing for a more reliable repair. These patients should be referred to a shoulder surgeon early.

KEY POINTS:

In general, it is highly unusual for a patient under 40 to have a rotator cuff tear without preceding trauma.

A young patient with a history of trauma followed by an inability to raise the arm or shoulder weakness needs early referral to a shoulder surgeon.

HOW DO I CLINICALLY DIAGNOSE A CUFF TEAR?

A combination of history and physical exam findings can lead to an accurate degree of clinical suspicion for a full-thickness rotator cuff tear. It is helpful to keep in mind the two groups described above.

Below are some of the history and exam findings that are most useful for distinguishing a full-thickness rotator cuff tear from other causes of shoulder pain.

1) Degenerative tear

History: night pain, problems sleeping, weakness of the shoulder or arm, difficulty getting dressed/undressed, difficulty reaching for a parking ticket or toll ticket (right shoulder).

Exam: tenderness of greater tuberosity area; positive Jobe test (supraspinatus); weak resisted external rotation strength (infraspinatus, possibly teres minor); weak internal rotation or a positive belly press test (subscapularis); pseudoparalysis; lag signs – thepatient’s arm is placed in external rotation/external rotation and abduction (hornblower’ssign)/forward elevation in scapular plane (drop arm sign) and the patient is unable to hold it there when the examiner lets go.

A patient with a negative Jobe test and a negative belly press test is unlikely to have a rotator cuff tear of any functional significance.

A patient with pseudoparalysis or lag signs has a massive rotator cuff tear that is likely to be irreparable; if surgery is to be considered it will be something other than repair.

Jobe’s test (supraspinatus) Pseudoparalysis of the right shoulder on attempted elevation

2) Traumatic tear

History: history of a distinct traumatic event that precipitated the shoulder pain; weakness; night pain.

Exam: Clinical exam of the shoulder in younger patients can have poor sensitivity, however a full-thickness rotator cuff tear will have weakness on Jobe’s test (or if an isolated subscapularis tear, on belly press test). This weakness may be subtle in a strong, male patient, but is usually detectable by testing both sides for comparison.

Belly press test for subscapularis. The examiner should not be able to overcome an intact subscapularis and should not be able to externally rotate the forearm away from the belly when the patient is resisting this action.

WHO NEEDS AN MRI?

Every painful shoulder does not need an MRI!

When there is definite weakness on exam, either on Jobe test, external rotation, or belly press test, then suspicion for a full thickness rotator cuff tear is high and an MRI is appropriate. A shoulder with fully intact rotator cuff strength on exam does not need an immediate MRI, and may well never need an MRI if symptoms settle with conservative measures.

A suspected rotator cuff tear in an older patient may also not be appropriate for MRI, because healing rates of rotator cuff repairs in patients aged over 75 are very low and therefore repair is often not performed. In a massive rotator cuff tear (pseudoparalysis, lag signs), rotator cuff repair will not be an option and the surgical solution, if the patient desires surgery, will be a reverse shoulder arthroplasty (see below), for which X-rays are the best initial imaging study.

It is sometimes helpful to ask the patient: “If we find something on MRI that could be fixedwith surgery, would you have surgery?” If the answer is “No, definitely not” (often the case with older patients), then the MRI is not useful! The exception to this approach is the young patient with a suspected traumatic rotator cuff tear – these patients need to be strongly encouraged to pursue imaging and surgical management if clinical suspicion is confirmed on MRI.

The downside to getting unnecessary MRIs is that the MRI is a sensitive test that often hasmany findings of limited clinical significance. The patient will often see the word “tear” inthe report and be convinced they need surgery, not understanding that the “possible, small,partial tear of supraspinatus” is completely insignificant functionally if they have a negative Jobe test on exam. In addition, there are some cases in which an alternative study would have been preferred by the shoulder surgeon (for example, a CT scan in a patient with a massive cuff tear for pre-operative planning for a reverse shoulder arthroplasty) but because an MRI has already been done, there is difficulty accessing another study or getting financial coverage for that study.

KEY POINT:

Exam comes before MRI. MRI is not a substitute for a focused clinical exam of the shoulder. If in doubt, check with the shoulder surgeon what imaging is appropriate or simply refer the patient to the shoulder surgeon.

WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF CUFF TEAR?

Rotator cuff tears may be partial or full thickness. Occasionally, a partial tear may come to surgery, typically in a high-level competitive athlete or other high demand patient, andusually only after conservative measures have failed to resolve the patient’s symptoms.

Full thickness tears may be small (<1cm), medium (1-3cm), large (3-5cm), or massive (>5cm), and this is only truly defined at surgery after debridement of the surrounding bursal tissue. In addition, full thickness tears can be described according to the shape or tear pattern as crescent, trapezoidal, U-shaped, L-shaped etc. The pattern of the tear influences the specific technique of repair.

Examples of rotator cuff tear patterns

DOES EVERY CUFF TEAR NEED TO BE FIXED?

Not all cuff tears will go on to rotator cuff repair surgery. In general, traumatic tears in young patients should undergo early repair. Many older patients have asymptomatic rotator cuff tears and have compensated well functionally by use of surrounding muscles. The rotator cuff tendons do not heal themselves, but in some cases, it is possible to convert a symptomatic tear to an asymptomatic tear with conservative measures such as anti- inflammatory medications, subacromial corticosteroid injections and physiotherapy.Depending on an individual’s level of function and age, it may be reasonable to trial a course of conservative management for a chronic, degenerative tear, before performing surgical repair.

WHAT DOES ROTATOR CUFF REPAIR INVOLVE?

Rotator cuff repair surgery is most commonly done arthroscopically, through multiple, small (approx. 5mm) stab incisions. It is usually done under general anaesthesia, sometimes supplemented with an interscalene nerve block of the brachial plexus for additional pain control. It may be done as a day case or may involve a single night’s stay inhospital, depending on the individual patient.

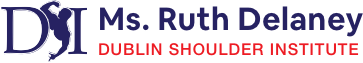

Diagnostic arthroscopy is performed both within the glenohumeral joint and in the subacromial space, and the tear size, shape and feasibility of repair are evaluated. If there is a subscapularis tear, this is effectively a separate entity from the rest of the cuff (the posterosuperior cuff), and the subscapularis is usually repaired first, while still working in the glenohumeral joint space. A thorough subacromial bursectomy is then performed to facilitate viewing of the posterosuperior cuff tear and to make space to carry out the repair. An acromioplasty is often performed as part of the subacromial decompression, particularly if there is a bony spur or hooked shape to the acromion. Suture anchors are then inserted in the area of the normal, anatomic rotator cuff insertion. The sutures are passed through the rotator cuff tendon using one of a variety of arthroscopic devices, and the tendon is brought back down to its insertion. A second, more lateral row of anchors may be used if a double row repair is being performed. There is no clear consensus in the literature as to whether the biomechanically beneficial effects of double row repair seen in some studies actually translate into clinical benefit.

Post-operatively, the patient is in a sling for 4-6 weeks, followed by a prolonged period of rehabilitation. Progress is gradual, and in general it takes 6-12 months for most patients to derive maximum benefit from the surgery. Pre-operative discussion of this post-operative course with the patient is an important responsibility of the surgeon. The surgery is successful in about 80% of patients in terms of patient satisfaction and clinical outcome scores.

Repaired rotator cuff tendon with sutures from anchor

ARE THERE ANY OTHER SURGICAL OPTIONS?

For massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears where there is fatty atrophy of the muscle and no reasonable likelihood of achieving a repair, there are still some surgical options available when conservative measures have failed.

If the problem is predominantly pain, many patients will get relief from a subacromical decompression, acromioplasty, and possibly from release of the suprascapular nerve, which can be tethered at the suprascapular notch of the scapula in a massive, retracted rotator cuff tear. The suprascapular ligament runs above the nerve in the suprascapular notch, somewhat analogous to the carpal tunnel, and nerve compression at this site can be a source of pain in massive rotator cuff tears.

Image from www.bosshin.comSchematic image of suprascapular nerve compression

If weakness and lack of function are problematic, with or without pain, a reverse shoulder arthroplasty may be an option. This is a type of shoulder replacement in which the ball and socket geometry is reversed, such that the ball component is placed on the glenoid side (glenosphere) and the socket component (cup) is on the humeral side. This enables the deltoid muscle to effectively take over the functions of the rotator cuff and restores the ability to raise the arm. This prosthesis does not withstand high impact activities or heavy loading, and is not usually advisable for younger, high demand patients.

Ms. Ruth Delaney. 2015.